斯诺精神

——纪念斯诺逝世二十周年

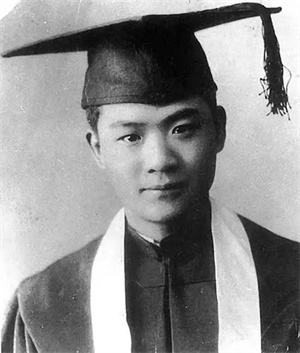

◎ 萧乾

我一生有过几次幸运和巧遇[1],其中之一是三十年代当上了斯诺的学生。当时他的本职是任英美两家报纸驻北平的记者。一九三三至一九三五年间,他应聘在燕京大学新闻系兼了课。斯诺仅仅在燕大教了这两年书,而我恰好就在那两年由辅仁大学的英文系转到了燕京大学的新闻系。我毕业后,他也辞去这个兼差,去了延安并写出他的杰作《红星照耀中国》——即《西行漫记》。

当时燕大教授多属学院派[2],不管教什么,都先引经据典,在定义上下功夫。而且,大都是先生讲,学生听。课堂上轻易听不见什么讨论。斯诺则不然。他着重讲实践,鼓励讨论。更重要的是,他是通过和同学们交朋友的方式来进行教学。除了课堂,对我们更具吸引力的,是他在海淀住宅的那座客厅。他和海伦都极好客,他们时常举行茶会或便餐,平时大门也总是敞着的[3]。一九三五年春天,正是在他那客厅里,我第一次见到了史沫特莱。当时,由于怕国民党特务找她的麻烦,她故意隐瞒了自己的真实姓名。斯诺约我去吃晚饭时,就介绍她作“布朗太太”。那阵子我正在读她的《大地的女儿》。因此,席间我不断谈到那本书给予我的感受。其实我并不知道坐在我旁边的就是那本书的作者。及至史沫特莱离平返沪后,斯诺才告诉我,那晚我可把史沫特莱窘坏了。她以为我把她认了出来。

在读新闻系时,我有个思想问题:我并不喜欢新闻系,特别是广告学那样的课,简直听不进去。我只是为了取得个记者资格才转系的[4]。我的心仍在文学系——因此,常旷了新闻系的课去英文系旁听[5]。斯诺帮我解决了这个矛盾。他说,文学同新闻并不相悖,而是相辅相成的。他认为一个新闻记者写的是现实生活,但他必须有文学修养——包括古典文学修养。我毕业那天,他和海伦送了我满满一皮箱的世界文学名著,由亚里士多德至狄更斯。他去世后,我从露易丝·斯诺的书中知道,他临终时,枕边还放着萧伯纳的著作。斯诺教导我,当的是记者,但写通讯特写时,一定要尽量有点文学味道。

一九三六年当他晓得我给《大公报》所写的冯玉祥访问记被国民党检查官砍得面目皆非——冯将军的抗日主张全部被砍掉了,他立即要我介绍他去访问这位将军——不出几天,我就在报上看到日本政府向南京抗议说,身居军事委员会副委员长的冯玉祥,竟然向美国记者斯诺发表了不友好的谈话。

一九四四年,我们又在刚刚解放的巴黎见了面。当时他是苏联特许的六名采访东线的记者之一。在酒吧间里他对我说,他在中国的岁月是他一生最难忘,也是最重要的一段日子。他自幸能在上海结识了鲁迅先生和宋庆龄女士。他是在他们的指引下认识中国的。

三十年代上半叶,在西方人中间,斯诺最早判断抗日战争迟早必然爆发,而且胜利最后必然属于中国。一九四八年,他又在《星期六评论》上接连写了三篇文章,断言中国战后绝不会当苏联的仆从,必然会走自己的路。他这种胆识,这种预见性,是难能可贵的。

斯诺认为一个记者绝不可光追逐热门新闻,他还必须把人类的正义事业记在心头。不能人云亦云,随波逐流,必须有自己独立的见解观点,必须有良知和正义感。

斯诺的骨灰一部分已留在中国了。我希望他的这种抱负和精神,也能在中国生根。

萧乾所著《斯诺精神》一文原载1992年7月3日《人民日报》。

[1]“我一生有过几次幸运和巧遇”译为I owe several happy events in my life to a lucky chance,其中把“幸运”和“巧遇”合并起来译为a lucky chance;又happy events(快事)是译文中的添加词,原文虽无其词而有其意,也可用delightful happenings表达此意。

[2]“当时燕大教授多属学院派”译为In those days, professors at Yenching University were mostly an academic type。原文“多属学院派”含意应为“大都是学究式人物”,可译为were mostly an academic type或were mostly academically-inclined。

[3]“平时大门也总是敞着的”不宜按字面直译为 They would usually leave the door wide open,现译为They would usually keep open house for us,其中to keep open house是成语,作“随时欢迎来客”解。

[4]“我只是为了取得个记者资格才转系的”译为 Frankly, I had transferred myself to the journalism department of Yenching for the sole purpose of obtaining qualifications for a reporter,其中Frankly(坦白说)是译文中的添加词。

[5]“我的心仍在文学系——因此,常旷了新闻系的课去英文系旁听”译为 Now, with my heart in literature, I often cut journalism classes so as to sit in on English literature classes,其中to cut作“旷(课)”解,to sit in on是成语,作“旁听”解。

Spirit of Edgar Snow

— Marking the 20th Anniversary of Snow’s Death

I owe several happy events in my life to a lucky chance. One of them was when I became a student of Edgar Snow’s in the 1930s. He was then a reporter for two foreign newspapers in Peiping, owned respectively by Britons and Americans. From 1933 to 1935, he was concurrently a teacher at the Journalism Department of Yenching University. During the two years when he was with this University, I happened to be a student there, having been previously transferred from the English Department of Catholic University in Peiping. Upon my graduation, he resigned the concurrent job and went to Yan’an where he wrote his masterpiece Red Star Over China.

In those days, professors at Yenching University were mostly an academic type. Whatever they taught, they would, first of all, give copious references to the classics and spend very much time on definitions. More often than not, they did all the talking while the students did nothing but listen. There was practically no classroom discussion at all. Snow, however, did otherwise. He gave priority to practice and encouraged discussion. And more importantly, he did teaching by way of making friends with his students. We found the reception room in his Haidian residence more appealing than the classroom. He and his wife Helen were very hospitable and often entertained us with tea or potluck. They would usually keep open house for us. In the spring of 1935, it was in that reception room that I met Agnes Smedley[1] for the first time. At that time, in order to steer clear of harassment by KMT agents, she had changed her name to conceal her true identity. So, the evening when I had dinner at Snow’s residence, he introduced her to me as“Mrs. Brown.”As it happened that I was then reading her novel Daughter of Earth, I kept talking at table about my impressions of it, not knowing that the very lady sitting next to me was its author. It was not until Smedley had left Peiping for Shanghai that Snow told me how apprehensive she had been that evening when I chatted about the novel, suspecting that I already knew her true identity.

While at Yenching University, I had a problem weighing on my mind: I found the study of journalism not to my liking and the advertising course particularly boring. Frankly, I had transferred myself to the journalism department of Yenching for the sole purpose of obtaining qualifications for a reporter. Now, with my heart in literature, I often cut journalism classes so as to sit in on English literature classes. Snow helped me solve this problem. He told me that instead of being contradictory to each other, literature and journalism were mutually complementary and that in order to write stories of real life, a newsman must be cultured in literature, including classical literature. On my commencement day, he and Helen gave me a suitcaseful of world literary classics, ranging from Aristotle to Dickens. Later I learned that when he was on his deathbed, a copy of Bernard Shaw’s work had been found lying by his pillow. I am greatly indebted to Snow for his teachings that literary taste is a must for a reporter’s news dispatches and feature articles.

In 1936, when Snow found in The Dagong Bao that the KMT had heavily censored my article Interview with Feng Yu-xiang[2], with Feng’s anti-Japanese views completely cut out, he wanted me immediately to introduce him to Feng for a visit. A few days later, I found in the newspapers that the Japanese government had protested to the KMT government about the unfriendly remarks from Military Commission Vice-Chairman Feng Yu-xiang in an interview with the American reporter Snow.

In 1944, Snow and I met again, this time in Paris shortly after its liberation. He was then one of the six reporters specially permitted by the Soviet Union to cover the east front. He told me in a barroom that the days he had spent in China were his most unforgettable experience and also the most important part of his life. He thought that he was most fortunate in having got acquainted with Lu Xun and Madame Soong Ching Ling in Shanghai and that it was through their guidance that he had come to understand China.

In the early 1930s, Snow was the first Westerner to predict that the War of Resistance Against Japanese Aggression would break out sooner or later and that the final victory would certainly belong to China. In 1948, he wrote three articles at a stretch for The Saturday Review, in which he stated with certainty that the post-war China would follow its own course and never become a Soviet flunkey. His courageous foresight was highly commendable.

He believed that a journalist should bear in mind the just cause of humanity instead of going after sensational reporting and that he should have independent views, good conscience and sense of justice instead of parroting other people’s opinions and following them blindly.

Part of Snow’s ashes now rest in China. I hope his aspirations and spirit will also take root in this country.

[1]Agnes Smedley (1892—1950), an American woman journalist and writer known for her sympathetic chronicling of the Chinese revolution. During the 1930s, she traveled with the Eighth Route and New Fourth Armies on China’s battlefields.

[2]Feng Yu-xiang (1882—1948), renowned Chinese general and patriot.

忆滇缅路

◎ 萧乾

在二次大战的众多深刻教训中,最主要也是最痛心的一条是:国与国之间平时客客气气[1],谁有点小灾小祸[2],还会略表支援;然而一个国家一旦自身遇到麻烦,需要出卖朋友来摆脱困境时,则什么背信弃义的勾当都干得出[3]。一九四〇年七月,正当我国抗战面临紧要关头,丘吉尔就为了讨好日本帝国主义[4]以保全英帝国在远东的殖民地[5],竟然在当时仍是英属缅甸边界,把抗战中国的这条生命线封锁。当时,除了横越喜马拉雅山的空运[6]外,我国所有进口的军火、汽油、药品、器械以及为换取这些而出口的钨砂、猪鬃、水银和桐油,都要经由这条公路运输。汽车行驶高峰每日达七千余辆,进出口物资达数百万吨。英国悍然封锁该公路扼住我们的咽喉,无疑是对我国一巨大打击。

一九三九年春间,我曾踏访了这条公路并曾为香港《大公报》写过几篇报道。其中,在《血肉筑成的滇缅路》一文中,我扼要地介绍了这条公路工程之艰巨:

九百七十三公里的汽车路,三百七十座桥梁,一百四十万立方尺的石砌工程,近两千万立方公尺的土方,不曾沾过一架机器的光,不曾动用巨款,只凭二千五百万名民工的抢筑:铺土、铺石,也铺血肉。下关至畹町那一段一九三七年一月动工,三月分段试车,五月就全面通车了。

路是沿着古老的通往印度和缅甸的马帮驿道修成的。为了修那条公路三千多人捐了躯。不能忘记的还有陈嘉庚组织的“南洋机工队”三千二百人,其中有一千多人在公路上为国殉难,除了工程的艰险之外,还有那怕人的瘴气——恶性疟疾[7]。同行的一位头天晚上还有说有笑[8],第二天一摸,全身凉了。我们当时是席地睡在一座马厩里,他就睡在我身旁。

一九三九年九月,我去了英国,正赶上二次欧战的爆发。没想到次年七月,我亲眼看到修筑的滇缅路被丘吉尔主持的英战时政府悍然封锁了,而且是在日本侵略者指使下这么干的,当时英国民间组织援华委员会就在全英掀起反封锁的运动。由于我是刚从抗战中国来到英国的记者,又曾采访过滇缅路,所以就应邀赴英国各大城市及乡村去演讲[9]。有些城市的英国群众还上街游行。在伦敦,援华会就曾组织人们到丘吉尔所在的唐宁街首相府门口摇旗呐喊,反对英国助桀为虐,帮助日本侵略者扼杀抗战的中国。

十月,英政府被迫解除了对滇缅路的封锁。一九四一年十月,中英签订了“共同防御滇缅路协定”。“珍珠港事变”后,中国军队就同盟军并肩作战于朱红色的滇缅土地上了。

滇缅路如今只是全国千百条公路中的一条了。可是当时中华民族的命运曾系在它身上。

《忆滇缅路》是萧乾于1995年根据五十多年前旧作《血肉筑成的滇缅路》写的一段二战史事,追忆当年中国劳工奋勇抢建我国生命线——滇缅路——的英雄事迹,并谴责英国战时政府在日本指使下一度悍然封锁该公路,助纣为虐,为虎作伥。

[1]“平时客客气气”意即“也许表面上彬彬有礼”,可译为may be formally polite。

[2]“小灾小祸”可译为a minor mishap或mishap,其中mishap原指“不太严重的灾难”。

[3]“什么背信弃义的勾当都干得出”译为it may stop at nothing to act perfidiously,其中to stop at nothing是成语,作“不顾一切地”、“不择手段地”解。

[4]“讨好日本帝国主义”意即“巴结日本侵略者”,可译为fawning on(或pleasing)the Japanese aggressors。

[5]“保全英帝国在远东的殖民地”译为to hold on to the British colonies in the Far East,其中to hold on to是成语,作“紧抓不放”、“不肯放弃”等解。

[6]“横越喜马拉雅山的空运”译为the airlift over the Himalayas,其中airlift作“(紧急情况下的)空运”或“空中补给线”解,意同(emergency)transport by air。

[7]“除了工程的艰险之外,还有那怕人的瘴气——恶性疟疾”可按“可怕的恶性疟疾是工人面临的诸多险情之一”译为The horrible disease of pernicious malaria was one of the great perils facing the laborers,其中“瘴气”就指“恶性疟疾”,可避而不译。

[8]“有说有笑”译为chatted and laughed merrily,其中merrily是译文中的添加词,原文虽无其词而有其意。

[9]“由于我是从抗战中国来到英国的记者,又曾采访过滇缅路,所以就应邀赴英国各大城市及乡村去演讲”译为As I was a Chinese correspondent just arrived in England from covering the Yunnan-Burmese Road, I was invited to deliver speeches in big cities and villages of the country,其中arrived是arrive的过去分词,作形容词用;covering作“采访”、“报导”解。

Recalling the Construction of the Yunnan-Burmese Road

◎ Xiao Qian

Of all the numerous profound lessons we have learned from World War II, the following is the most distressing. A country may be formally polite to another and show willingness to offer it a little help in case of a minor mishap befalling the latter. But it may stop at nothing to act perfidiously when it seeks to extricate itself from its own predicament at the expense of its friend. In July 1940, at the critical juncture of China’s Anti-Japanese War, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill, endeavoring to hold on to the British colonies in the Far East by fawning on the Japanese imperialists, ordered a blockade of our lifeline on the Burmese side of the border with China, Burma then being a British colony. At that time, in addition to the airlift over the Himalayas, it was through the land transport by the Yunnan-Burmese Road that China imported munitions, gasoline, medicines and appliances in exchange for such exports as tungsten ore, hog bristles, mercury and tung oil. The Road daily witnessed a traffic of over 7,000 motor vehicles during the peak hours and the transport of several million tons of import and export goods. Britain’s brazen act of blockading the Road meant, as it were, grabbing our throat. It was undoubtedly a serious blow to China.

In the spring of 1939, I wrote several reports for the Hong Kong Dagong Bao after making an on-the-spot investigation of the Road. In one of them, entitled The Yunnan-Burmese Road — Paved with Flesh and Blood, I gave as follows a brief account of the formidable Road building project:

A 973-kilometer motorway, with 370 bridges, 1,400,000 cubic meters of stone work, and approximately 20,000,000 cubic meters of earth work. With neither machines nor adequate funds, 25 million laborers were engaged in a rush job of road construction. They paved the road with flesh and blood as well as with earth and stone. Work on the Xiaguan-Wanding section of the road started in January 1937 and was entirely opened to traffic in May after a section-by-section trial run in March.

The Road was built on the ancient post road leading to India and Burma, on which caravans used to travel. More than 3,000 men laid down their lives for building the Road. Of the 3,200 members of the“Nanyang Mechanics Team”organized by Tan Kah-kee[1], over 1,000 died on the job. The horrible disease of pernicious malaria was one of the great perils facing the laborers. One of my fellow travelers who chatted and laughed merrily one evening and then slept next to me on the ground of a stable was found stiff and cold the next day.

In September 1939, World War II broke out on my arrival in England. Unexpectedly, the wartime British government under Churchill, on the instigation of the Japanese aggressors, outrageously blockaded in July 1940 the Yunnan-Burmese Road, whose construction I had just seen with my own eyes. Britain’s non-governmental Aid-China Committee then launched a nationwide anti-blockade campaign. As I was a Chinese correspondent just arrived in England from covering the Yunnan-Burmese Road, I was invited to deliver speeches in various big cities and villages of the country. In some cities, people even demonstrated in the streets. In London, the Aid-China Committee organized people to demonstrate in front of Churchill’s official residence on Downing Street, waving flags and shouting slogans decrying the British government aiding Japanese aggression against China.

In October of the same year, the British government was compelled to lift its blockade of the Road. In October 1941, China and Britain signed the“Agreement on the Joint Defence of the Yunnan-Burmese Road.”After the Pearl Harbor Incident of December 7, 1941, Chinese troops began to fight shoulder to shoulder with the Allied troops on the red earth field surrounding the Road.

Now the Road is but one of the thousands of highways in China. But back in those days, it had a close bearing on the destiny of the Chinese nation.

[1]Tan Kah-kee (1874—1961), a well-known patriotic leader of overseas Chinese in Singapore dedicated to national salvation, entrepreneurship, philanthropy, social reform and education.