One hears, it’s said, Chang’an is a game of chess

A century of events beyond sorrow

Where princely palaces have new owners and

Civilian and military clothes have changed from the past

To the north of the mountain pass, gongs and drums sound

In the western campaign, wagons and horses and feathered dispatches are slowed

The dragons and fish are lonely, the autumn river is cold

My thoughts are always of the Motherland in peace

Motherland at War

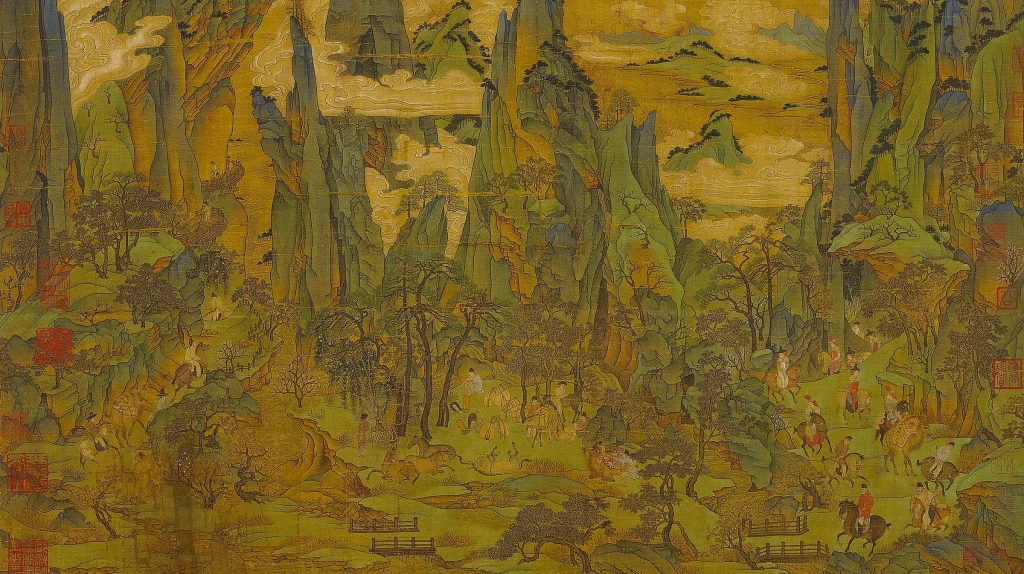

In 756, Chang’an, capital of the Tang dynasty, the largest empire in the world, fell to the rebel forces of General An Lushan.

The Imperial Chinese Emperor Xuanzong fled to Sichuan. There he abdicated in favor of his son, the new Emperor Suzong. Thereafter, between 757 and 763, Chang’an became a pawn in the battle between Imperial and rebel forces where moves and counter moves of the two armies were laid out as if on a chessboard. Flags were used in the day to signal troop movements. Gongs and drums were used at night, drums to attack, gongs to retreat. The continuous fighting went back and forth. Feathered dispatches indicated urgency, that is, thick and fast.

In war, delay spells the difference between success and failure in battle.

Chinese and Pinyin

秋兴八首 (四)

闻道长安似弈棋

百年世事不胜悲

王侯第宅皆新主

文武衣冠异昔时

直北关山金鼓振

征西车马羽书迟

鱼龙寂寞秋江冷

故国平居有所思

qiū xìng bā shǒu (sì)

wén dào cháng ān sì yì qí

bǎi nián shì shì bú shèng bēi

wáng hóu dì zhái jiē xīn zhǔ

wén wǔ yī guān yì xī shí

zhí běi guān shān jīn gǔ zhèn

zhēng xī chē mǎ yǔ shū chí

yú lóng jì mò qiū jiāng lěng

gù guó píng jū yǒu suǒ sī

Notes on translation

The Tang capital has fallen, the battle goes back and forth. Fleeing south, Du Fu is captured by the rebels and taken back to Chang’an where he witnesses the changes he writes about. He watches the horse drawn wagons lumber on and sees couriers with feathered dispatches flying off. Here and there one hears the reports of the campaign in the West (征西, zhēng xī).

One pauses for reflection at line seven.

Separately, the first two characters, 鱼龙 yú lóng, translate as fish and dragon. The dragon, 龙, the symbol of the Tang emperor, the fish, 鱼 , of his people. 寂寞 jì mò, each indicate loneliness, together to an extreme, i.e. desolateness. The line concludes with 秋江冷 qiū jiāng lěng, the autumn river is cold, a familiar motif in Tang poems indicating that life was coming to an end.