倘若我是一个日本人

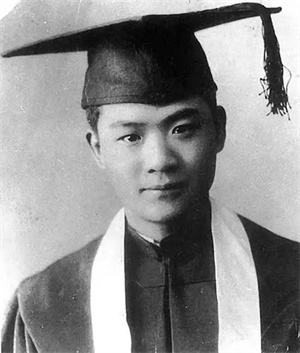

◎ 萧乾

倘若我是个日本人,一到这战争纪念日,我会难过[1],羞愧,在亚洲人民面前抬不起头来。倒不是由于五十年前打败了,而是五十年后对自家为千千万万的人们所带来的祸害,采取抵赖、死不认帐的态度[2]。在亚洲人面前(或是心目中),是个赖帐的。明明六十多年前是自家的关东军制造事端抢了邻人的东北大片土地,五十多年前又从卢沟桥掀起东亚大战。太阳旗所到之处,烧杀掠夺,生灵涂炭[3]。接着,又把战火推向东南亚以至大洋洲。皇军闯到哪儿,祸水就冲到哪儿。遍地留下了万人坑。可如今,连“侵略”两个字都不承认,说是“进入”!还把造成的地狱硬说成是“乐土”。

凡事都怕一比[4]。当年欧洲那些纳粹哥儿们[5]所造成的祸害也不小啊!光死在那些集中营的焚尸炉、毒气室,人体实验上的,就足有几百万。可是人家打败了仗,好汉做事好汉当。首先从上层就低头认罪,绝不抵赖。该作揖的作揖,该下跪的就下跪。欠下的帐,一五一十,分文不赖[6]。如今,在国际社会中,人家又挺起腰板,成为可以信赖、受到尊重的一员了[7]。多年来曾经首先受害的法国一直愉快地谈着法德友谊。可我当个日本人,只由于一提那场战争,上头就刁钻古怪,闪烁其辞[8],死不认帐。而且大官儿们还去给当年干尽坏事的头儿们的阴魂烧香磕头,等于感谢他们杀得好,杀得痛快、漂亮。不但对世界、对亚洲人耍赖,在教科书里,对儿孙们也撒谎、抵赖。站在二十一世纪的门坎,当个日本人,我忧心忡忡,而且抬不起头来。

然而我不是个日本人。

我是一个八十六岁饱经沧桑的中国老头儿。我周围的后生一提起日本对战争罪行死不认帐,就摩拳擦掌,怒火中烧,我这世故老汉儿倒是处之泰然。凡事都有两个方面。我认为今天日本不认罪也就是思想上还没放下屠刀,东条还在阴魂不散,谁敢担保在下个世纪他不会借尸还魂!它的徘徊等于时刻在提醒我们——以及亚洲弟兄们,不要以为今后就天下太平可以高枕无忧了。

我不晓得靖国神社里敲不敲钟。倘若敲的话,对军国主义的崇拜者们,那是为了悼念当年侵略者的“英”灵,对我们——中国人和亚洲人,那钟声正好提醒我们,告诫我们千万不可睡大觉。世界眼下风平浪静,可是只要霸人之心不死,防霸之心就不可无[9]。一个输了而不认输的赌徒是随时可能卷土重来的。

萧乾所著《倘若我是一个日本人》一文原载1995年9月30日《新民晚报》。

[1]“难过”意同“歉疚”、“后悔”,故译to feel very bad。

[2]“倒不是……,而是……”意同“不是(因为)……,而是(因为)……,”可译为Not that …, but that …,或Not because …, but because …。

[3]“烧杀掠夺,生灵涂炭”译为burning, killing and looting would follow and people would be plunged into the abyss of untold suffering。“生灵涂炭”意同“老百姓遭殃”,故译and people would be plunged into the abyss of untold suffering(或extreme misery)。

[4]“凡事都怕一比”可按“只有通过比较才能判别是非”译为Only by comparison can we distinguish between right and wrong。

[5]“纳粹哥儿们”译为Japan’s Nazi buddies,其中buddies作“伙伴”、“搭档”解。

[6]“欠下的账,一五一十,分文不赖”可用意译法灵活处里:They owned up to everything they had said or done,其中to own up to是成语,作“坦白地承认”解。

[7]“如今,在国际社会中,人家又挺起腰板,成为可以信赖、受到尊重的一员了”译为Consequently, standing erect and with chin up, they have won the trust and respect of the world community of nations,其中“挺起腰板”译为standing erect and chin up,比按字面直译成straightening their backs(或with their backs straightened)更为传神达意。

[8]“一提那场战争,上头就刁钻古怪,闪烁其辞”译为my higher-ups’ tricky hems and haws on the subject of the last war,其中hems and haws的意思是“说话吞吞吐吐”、“搪塞不表态”等。

[9]“只要霸人之心不死,防霸之心就不可无”译为vigilanc e is indispensably necessary before the potential hegemonist is completely disillusioned。“只要霸人之心不死”可按“只要潜在的霸权者仍抱幻想”译为before the potential hegemonist is completely disillusioned。

If I Were a Japanese

◎ Xiao Qian

If I were a Japanese, I would, on this war commemoration day, feel very bad and ashamed, and keep my head bowed before the people of Asia. Not that Japan was defeated 50 years ago, but that it today persists in denying the disaster it brought upon millions upon millions of common people. In the eyes of all Asians, Japan remains absolutely unrepentant. As is known to all, over 60 years ago, the Japanese Guandong Army occupied by making a pretext the vast expanse of land in Northeast China[1], and over 50 years ago Japan started the War of East Asia by staging the Lugou Bridge Incident[2]. Wherever the flag of the Rising Sun fluttered, burning, killing and looting would follow and people would be plunged into the abyss of untold suffering. And then Japan spread the flames of war to Southeast Asia and even Oceania. The Japanese Imperial Army left behind great destruction and mass graves everywhere. And yet they now describe their acts of aggression euphemistically as“making an entry”and insist on calling the hell of their doing by the good name of“land of happiness”!

Only by comparison can we distinguish between right and wrong. Japan’s Nazi buddies during WWII brought equally frightful calamity to Europe, killing, for instance, at least a total of several million people in the concentration camps by means of crematories, gas chambers and vivisection. Nevertheless, after Germany was defeated, the Germans had the courage to accept the consequences of their own actions. They, from top to bottom, hung their heads to admit their guilt rather than deny facts. They bowed with hands clasped or went down on their knees. They owned up to everything they had said or done. Consequently, standing erect and with chin up, they have won the trust and respect of the world community of nations. France, the first European country victimized by Nazi invasion, has now been happy for years about Franco-German friendship. As a Japanese, I would be disgusted with my higher-ups’ tricky hems and haws on the subject of the last war and their flat refusal to acknowledge Japan’s crimes. Our bigwigs continue to burn incense and kowtow before the memorial tablets of the notorious war criminals — an act tantamount to expressing gratitude to slaughterers for massacring common people. They are telling lies not only to the Asians and the world at large, but also in school textbooks to mislead their own younger generations. As a Japanese at the turn of the century I would be heavy-hearted and unable to raise my head.

But I’m not a Japanese.

I’m an old man of 86 from China having experienced many vicissitudes of life. While the young folks around me will burn with rage at the mention of Japan’s stubborn refusal to own up, I, being a worldwise old man, will stay calm and collected. Everything, however, has two aspects. I think Japan’s refusal to admit its crimes is due to its failure to be mentally prepared to drop the butcher’s knife. So long as the ghost of Tojo lingers on, none can assure you that militarism will never revive in a new guise in the next century. The lingering shadow serves to warn us and our Asian brothers against the fantasy that the world will be at peace in the days to come and we can sit back and relax.

I wonder if the bell still strikes at Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo. If it does, it serves as a warning to the people of China and Asia not to drop guard while the adherents to militarism are mourning over their late war criminals. Although the world is tranquil for the time being, vigilance is indispensably necessary before the potential hegemonist is completely disillusioned. An adventurist that refuses to be reconciled to defeat may stage a comeback at any time.

[1]On the night of September 18, 1931, the Japanese Guandong Army seized Shenyang (formerly known as Mukden) of Liaoning Province by making a pretext, prior to their imminent occupation of the entire Northeast China (formerly known as Manchuria).

[2]Also known in the West as Marco Polo Bridge Incident. On July 1,1937, the Japanese invaders raided the Chinese garrison at the Lugou Bridge to the southwest of present-day Beijing, and the Chinese army rose in a counterattack, thus unveiling the War of Resistance Against Japan.